Figuring out how to bring great leaps of innovation to a large and long-running company can be a massive undertaking. However, that’s exactly what the team at Piaggio Fast Forward is doing.

Italian vehicle manufacturer Piaggio was established in Italy in 1882 and is, among other things, the maker of the world-famous and highly iconic Vespa scooter. Formed in 2015, Piaggio Fast Forward functions as an innovation lab within the larger corporation and works, to create “lightweight, intelligent, and autonomous mobility solutions.”

Their first product is Gita, which is a small, robotic cargo vehicle designed to move around inside buildings as well as outside on sidewalks and streets, assisting people and companies in transporting small goods.

Jesse Whitworth and Carlos Asmat are two of the engineers behind the robot.

Jesse joined as the lead full stack developer, with the goal of building out a web team and developing web-based products that supplement their robotic offerings. “Coming up with a website for controlling the robots, getting statuses, mapping, mobile apps to control the robot from your phone — that sort of thing. And then we’re also building out a website where you can build and order your own robot.”

Carlos is the lead robotics software engineer, and he came on board in June of 2016 to start the development of Gita’s software. “When I joined, the company was mainly focused on exploring urban mobility and finalizing the concept of Gita. At that point, my role evolved to encompass electrical and system aspects as we started making the robot. It took about nine months and many all-nighters from that point to get to the first public release of Gita.”

Read on to find out what they’ve learned from working on Gita.

A Startup Within A Company

According to Jesse, working as a small, independent team within a large, established company is no different than working at any other startup in terms of the urgency to release a product and prove yourself in the market.

However, Piaggio’s 135-year existence means that Fast Forward is able to leverage that structure, rather than doing everything from scratch. While they do have to occasionally negotiate the intersection of tradition and innovation as they modernize the company and brand, the team appreciates being able to draw on the ample skill and experience that have helped Piaggio succeed for so very long.

He adds, “The best part of being part of a larger organization, is being able to lean on the expertise, tools, and business contacts of the people that have come before you. At Piaggio Fast Forward, we’re lucky to have an incredibly supportive organization that trusts us to find new solutions to urban mobility.”

Self-Managed Teams

Once Jesse had a plan for developing Fast Forward web applications, he started to implement Scrum with his team. The upside of Scrum for Jesse is that it’s extremely simple to pick up, yet very powerful — “you can read the guidelines in less than thirty minutes and have a good understanding of it.”

He’d been at places in the past where Agile was implemented in a way that he found less than useful. When he joined the Piaggio Fast Forward team, the company had already been working in a way that was similar to Scrum, just less formalized. “They would give the team high level features, and everyone was expected to figure out how to do them, iterate on their solutions, and create the best solution.”

For Jesse, the idea of letting the team come up with the answers to product problems is important. “I’ve been at other places where Agile was implemented, but the only thing that was followed was having a two-week sprint and estimates for tasks.”

Carlos also prefers a similar style of self-driven work:

“As our team has grown, we have an increasing need for organization, but in general, every member of the team gets a high-level task, like ‘detecting obstacles.’ From there, that member is responsible for breaking it down into chunks that make sense and working through them.”

He continues, “Of course, we’re all working together and communicating about our work, seeing how things are getting done and keeping track of timelines. But, in general, everyone gets to decide how a task should be tackled, and that’s been working very well — everyone is very responsible and talented, so we like to trust them with the technical decisions and their expertise.”

{{testimonial-component}}

When the Software Meets the Road

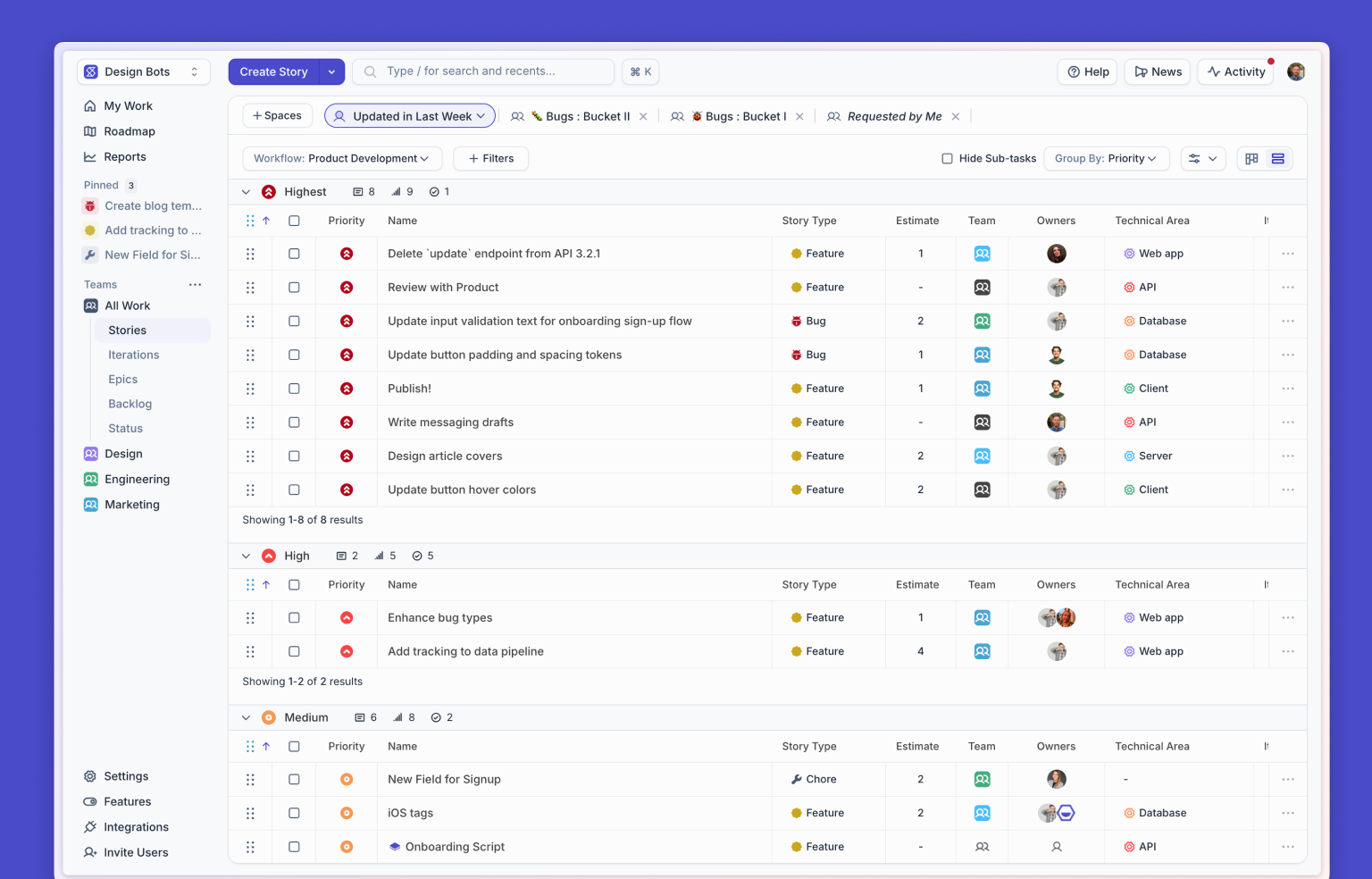

For products like Gita, there’s a lot of cross-functional collaboration. The web team and the robotics software team do daily stand-ups together, but have also implemented Milestone meetings. “We treat our Milestones in Shortcut as a vision document, and then get all of the team leads together with the management team that’s driving the vision of the product. We talk about everything we’ll accomplish in a quarter and lay it all out, making sure everyone understands and can ask all the questions they need to.”

After the larger Milestone document is created, it’s up to the individual teams to break it down into Epics, with each Epic being assigned to a team member. That person is then responsible for creating the stories that go under the Epic.

“Once all of that has happened, we have a pretty good estimate of how long that Milestone will take, and we use the burndown chart and estimates features to help us track that,” says Jesse.

Working on a project that has both a hardware and a software component presents its own unique challenges. Interfaces are a big part of what the teams work on together; it’s important that the robot is sending data in a way that’s accessible to the web apps and tools (and can be displayed in a readable manner).

They also must be in tight coordination to ship on time. “When there’s very tight integration between hardware and software, and the hardware is much slower to create, coordinating the timelines between them is a little challenging,” notes Carlos.

Progress, Not Perfection

They’ve had to make a few adjustments to workflows along the way to account for these differences. For example, everyone works in two-week sprints, even the hardware teams — but having something deliverable on the hardware side within two weeks is often a little “over-optimistic,” as Carlos puts it. Because of this, they’ve adjusted the process so the focus is less on deliverables, and more on being able to show concrete progress over sprints.

Working with robotics can also add some interesting twists and turns in the process. “Sometimes, the tests will pass in the computer, and work in the simulator, but when we actually test on the robot — which is the final step to us completing any task — the robot doesn’t perform the way we want,” says Carlos.

Jesse, who previously worked in more traditional software settings, adds:

“Another thing is that when we do the tests on the robots, the tolerances are fairly wide because we’re often working on prototype hardware. Each robot is unique, with slightly different characteristics, which means that testing on one robot could yield different results than testing on another robot. That makes it challenging in a very different way than booting up a virtual machine and running your code in exactly the environment you want, whenever you want.”

Do you work at an older, more traditional company? How have you been able to introduce new ideas? We’d love to hear your answers on Twitter.

.png)

%20(788%20x%20492%20px)%20(1).png)

.png)